Innovation can be defined simply as a "new idea, device or method".

[1] However, innovation is often also viewed as the application of better solutions that meet new requirements, unarticulated needs, or existing market needs.

[2] This is accomplished through more-effective

products,

processes,

services,

technologies, or business models that are readily available to

markets,

governments and

society. The term "innovation" can be defined as something original and more effective and, as a consequence, new, that "breaks into" the market or society.

[3] It is related to, but not the same as,

invention.

[4] Innovation is often manifested via the

engineering process. The opposite of innovation is

exnovation.

While a novel device is often described as an innovation, in economics, management science, and other fields of practice and analysis, innovation is generally considered to be the result of a process that brings together various novel ideas in a way that they affect society. In

industrial economics, innovations are created and found empirically from services to meet the growing

consumer demand.

[5][6][7]

Definition

Innovation is: production or adoption, assimilation, and exploitation of a value-added novelty in economic and social spheres; renewal and enlargement of products, services, and markets; development of new methods of production; and establishment of new management systems. It is both a process and an outcome.

Two main dimensions of innovation were degree of

novelty (patent) i.e. whether an innovation is new to the firm, new to the market, new to the industry, and new to the world and type of innovation, whether it is process or

product-service system innovation.

[8]

Inter-disciplinary views

Business and economics

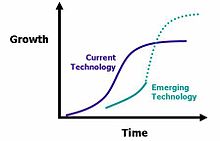

In business and economics, innovation can be a catalyst to growth. With rapid advancements in

transportation and

communications over the past few decades, the old world concepts of

factor endowments and

comparative advantage which focused on an area’s unique inputs are outmoded for today’s

global economy. Economist

Joseph Schumpeter, who contributed greatly to the study of

innovation economics, argued that industries must incessantly revolutionize the economic structure from within, that is innovate with better or more effective processes and products, as well as market distribution, such as the connection from the craft shop to factory. He famously asserted that "

creative destruction is the essential fact about

capitalism".

[9] In addition,

entrepreneurs continuously look for better ways to satisfy their

consumer base with improved quality, durability, service, and price which come to fruition in innovation with advanced technologies and organizational strategies.

[10]

One prime example was the explosive boom of

Silicon Valley startups out of the

Stanford Industrial Park. In 1957, dissatisfied employees of

Shockley Semiconductor, the company of

Nobel laureate and co-inventor of the

transistor William Shockley, left to form an independent firm,

Fairchild Semiconductor. After several years, Fairchild developed into a formidable presence in the sector. Eventually, these founders left to start their own companies based on their own, unique, latest ideas, and then leading employees started their own firms. Over the next 20 years, this snowball process launched the momentous

startup company explosion of

information technology firms. Essentially, Silicon Valley began as 65 new enterprises born out of Shockley’s eight former employees.

[11] Since then, hubs of innovation have sprung up globally with similar

metonyms, including

Silicon Alley encompassing

New York City.

Another example is the

Business Incubators - a phenomenon that is nurtured by governments around the world, close to knowledge clusters, mostly research based, like universities or other Government Excellence Centres, while the main goal is to channel the generated knowledge to applied innovation outcomes in order to stimulate regional or national

economic growth.

[12]

Organizations

In the organizational context, innovation may be linked to positive changes in

efficiency,

productivity,

quality,

competitiveness, and

market share. However, recent research findings highlight the complementary role of organizational culture in enabling organizations to translate innovative activity into tangible performance improvements.

[13]Organizations can also improve profits and performance by providing work groups opportunities and resources to innovate, in addition to employee's core job tasks.

[14] Peter Drucker wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth. –Drucker

[15]

According to Clayton Christensen,

disruptive innovation is the key to future success in business.

[16] The organisation requires a proper structure in order to retain competitive advantage. It is necessary to create and nurture an environment of innovation. Executives and managers need to break away from traditional ways of thinking and use change to their advantage. It is a time of risk but even greater opportunity.

[17] The world of work is changing with the increase in the use of technology and both companies and businesses are becoming increasingly competitive. Companies will have to downsize and re-engineer their operations to remain competitive. This will affect employment as businesses will be forced to reduce the number of people employed while accomplishing the same amount of work if not more.

[18]

While disruptive innovation will typically "attack a traditional business model with a lower-cost solution and overtake incumbent firms quickly,"

[19] foundational innovation is slower, and typically has the potential to create new foundations for global technology systems over the longer term. Foundational innovation tends to transform business

operating models as entirely new business models

emerge over many years, with gradual and steady adoption of the innovation leading to waves of

technological and

institutional change that gain momentum more slowly.

[19] The advent of the

packet-switched communication protocol

TCP/IP—originally introduced in 1972 to support a single

use case for

United States Department of Defense electronic communication (email), and which gained widespread adoption only in the mid-1990s with the advent of the

World Wide Web—is a foundational technology.

[19]

All organizations can innovate, including for example hospitals, universities, and local governments.

[20] For instance, former Mayor

Martin O’Malley pushed the

City of Baltimore to use

CitiStat, a

performance-measurement data and management system that allows city officials to maintain statistics on crime trends to condition of

potholes. This system aids in better evaluation of policies and procedures with accountability and efficiency in terms of time and money. In its first year, CitiStat saved the city $13.2 million.

[21] Even

mass transit systems have innovated with

hybrid bus fleets to

real-time tracking at bus stands. In addition, the growing use of

mobile data terminals in vehicles, that serve as communication hubs between vehicles and a control center, automatically send data on location, passenger counts, engine performance, mileage and other information. This tool helps to deliver and manage transportation systems.

[22]

Sources

There are several sources of innovation. It can occur as a result of a focus effort by a range of different agents, by chance, or as a result of a major system failure.

According to

Peter F. Drucker, the general sources of innovations are different changes in industry structure, in market structure, in local and global demographics, in human perception, mood and meaning, in the amount of already available scientific knowledge, etc.

[15]

Original model of three phases of the process of Technological Change

In the simplest

linear model of innovation the traditionally recognized source is

manufacturer innovation. This is where an agent (person or business) innovates in order to sell the innovation. Specifically, R&D measurement is the commonly used input for innovation, in particular in the business sector, named Business Expenditure on R&D (BERD) that grew over the years on the expenses of the declining R&D invested by the public sector.

[23]

Another source of innovation, only now becoming widely recognized, is

end-user innovation. This is where an agent (person or company) develops an innovation for their own (personal or in-house) use because existing products do not meet their needs.

MIT economist

Eric von Hippel has identified end-user innovation as, by far, the most important and critical in his classic book on the subject,

The Sources of Innovation.

[24]

- A recognized need,

- Competent people with relevant technology, and

- Financial support.[25]

However, innovation processes usually involve: identifying customer needs, macro and meso trends, developing competences, and finding financial support.

The Kline

chain-linked model of innovation

[26] places emphasis on potential market needs as drivers of the innovation process, and describes the complex and often iterative feedback loops between marketing, design, manufacturing, and R&D.

Innovation by businesses is achieved in many ways, with much attention now given to formal

research and development (R&D) for "breakthrough innovations". R&D help spur on patents and other scientific innovations that leads to productive growth in such areas as industry, medicine, engineering, and government.

[27] Yet, innovations can be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of professional experience and by many other routes. Investigation of relationship between the concepts of innovation and technology transfer revealed overlap.

[28] The more radical and revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice – but there are many exceptions to each of these trends.

Information technology and changing business processes and management style can produce a work climate favorable to innovation.

[29] For example, the software tool company

Atlassian conducts quarterly "ShipIt Days" in which employees may work on anything related to the company's products.

[30] Google employees work on self-directed projects for 20% of their time (known as

Innovation Time Off). Both companies cite these bottom-up processes as major sources for new products and features.

An important innovation factor includes customers buying products or using services. As a result, firms may incorporate users in

focus groups (user centred approach), work closely with so called

lead users (lead user approach) or users might adapt their products themselves. The lead user method focuses on idea generation based on leading users to develop breakthrough innovations. U-STIR, a project to innovate

Europe’s surface

transportation system, employs such workshops.

[31] Regarding this

user innovation, a great deal of innovation is done by those actually implementing and using technologies and products as part of their normal activities. Sometimes user-innovators may become

entrepreneurs, selling their product, they may choose to trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations, or they may be adopted by their suppliers. Nowadays, they may also choose to freely reveal their innovations, using methods like

open source. In such networks of innovation the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and reinvent their social meaning.

[32][33]

Goals and failures

Programs of organizational innovation are typically tightly linked to organizational goals and objectives, to the

business plan, and to

market competitive positioning. One driver for innovation programs in corporations is to achieve growth objectives. As Davila et al. (2006) notes, "Companies cannot grow through cost reduction and reengineering alone... Innovation is the key element in providing aggressive top-line growth, and for increasing bottom-line results".

[34]

One survey across a large number of manufacturing and services organizations found, ranked in decreasing order of popularity, that systematic programs of organizational innovation are most frequently driven by: Improved

quality, Creation of new

markets, Extension of the

product range, Reduced

labor costs, Improved

production processes, Reduced materials, Reduced

environmental damage, Replacement of

products/

services, Reduced

energy consumption, Conformance to

regulations.

[34]

These goals vary between improvements to products, processes and services and dispel a popular myth that innovation deals mainly with new product development. Most of the goals could apply to any organisation be it a manufacturing facility, marketing firm, hospital or local government. Whether innovation goals are successfully achieved or otherwise depends greatly on the environment prevailing in the firm.

[35]

Conversely, failure can develop in programs of innovations. The causes of failure have been widely researched and can vary considerably. Some causes will be external to the organization and outside its influence of control. Others will be internal and ultimately within the control of the organization. Internal causes of failure can be divided into causes associated with the cultural infrastructure and causes associated with the innovation process itself. Common causes of failure within the innovation process in most organizations can be distilled into five types: Poor goal definition, Poor alignment of actions to goals, Poor participation in teams, Poor monitoring of results, Poor communication and access to information.

[36]